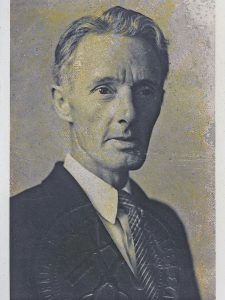

I don’t know why my father Donald Moncrief did what he did.

Perhaps it was a warped attempt to capture the history of his family that had been lost to him for the better part of his life. I loved my father; still, what he did on the day he finally returned to Emmetsburg, Iowa and visited St. John’s Cemetery, was abhorrent to me.

The Early Years

His own father, William, was by all accounts wild in his youth and a hard and restless drinker for the better part of his life. He left his wife and 5 children in 1924 and headed for Los Angeles – supposedly, to make a better life for all of them. Trouble was, once William arrived and settled in, he seemed to have forgotten to send for Mae and their children: Maurice, Donald, Mary, Deanne and Bernard.

Mae, with only a purse full of change, put herself and the kids on a train and set out to find her husband, William.

Emmetsburg was a very small town. Mae had never seen a big city. She and her troupe stepped off the train at Union Station in Los Angeles. She walked up to the first person she saw and asked, “Do you know William Moncrief?” She was surprised when the gentleman gave her only a blank stare.

Eventually, she sought help from a family-aid organization. It put her in touch with the Los Angeles Herald Examiner. The next morning, William – who was a barber by trade – was busy cutting hair when his customer opened the Herald, perused the photograph, and read the headline, “Do You Know This Man?”

As the story goes, he turned to William and said, “Ah, Bill, you might want to read this.”

Mae and William reunited for a few years. They even had another child together, but the marriage didn’t last.

My father, Donald, was only 7 when the family left Emmetsburg, but he remembered that train trip vividly all his life. He also remembered the street where they had lived, the look of the house, and the friends he had left behind. These images of that lost life were seared on his brain.

Return to Emmetsburg, Iowa

In the early Seventies, after they retired, my mother and father took numerous road trips, pulling their trailer; my mother writing her journals describing each stop along the way and my father reading his Zane Grey novels and searching for artifacts of the Old West.

Eventually, they tootled their way back to Emmetsburg. In addition to locating his old house and tracking down the families and friends he could still find, my father visited Emmetsburg’s Catholic Cemetery and re-discovered the graves of his grandparents, John and Mary and his great grandfather and grandmother, Thomas and Lucy. That’s when he saw the bronze star, and that’s when the twisted idea began to grow in his mind.

The Civil War Hero

According to his obituary printed in Emmetsburg’s Palo Alto Reporter, Thomas William Moncrief lived “a long and eventful life.” He was born in Queenstown, Ireland. At the age of 21, he entered the British service and fought in the First Carlist’s War in Spain (1834-1839). Returning home, he married Lucy Maynard in 1837.

In 1844, they emigrated from Ireland to St. John’s, New Brunswick. Three years later, they “abandoned her majesty’s dominions” and took up habitation in Portland, Maine. They then moved to Illinois in 1851. In the early autumn of 1864, he again forsook the peaceful pursuits of life and enlisted in the Union Army’s 146 Illinois Regiment, becoming a member of company F.”

After the war, Thomas yet again returned to peaceful pursuits. In 1874, he and the family moved to Emmetsburg, Iowa. In the mid-1880s, Thomas was elected mayor of the growing township and also served as its justice of the peace for many years.

The obituary concludes: Thomas “indeed had a long and eventful career, covering as it did a period of 81 years and participating in two of the memorable struggles of the 19th century.”

When Thomas died on December 23, 1895, he was buried next to Lucy in St. John’s Cemetery where he rested peacefully – at least until the day when my father arrived and visited his great-grandfather’s grave.

The site was graced by a bronze star with the words, “Civil War Veteran” inscribed at its center. The star, secured on an iron stanchion a half inch in diameter, was set in the ground adjacent to Thomas’ tombstone.

When my father saw this star, he decided that he wanted it for his own. He went into town, purchased a hacksaw, cut the iron stanchion, put the star in his coat pocket, and carried it back to California.

When I heard what he had done, I was appalled at the act; after all, Thomas was not only his great grandfather, he was my great-great grandfather. He was my children’s great-great-great grandfather. The violation touched the entire family and future generations who would never know about the bronze star, planted there in memory of their ancestor’s service and contribution to the preservation of the Union.

My father had appropriated to himself something sacred that belonged to all of Thomas and Lucy’s progeny.

Plans For Restitution

Forty years or more have passed since Donald Moncrief made off with this family heirloom. To be honest, I don’t remember confronting him about the deed although I probably did. I imagine him saying something like, “Horse feathers! What difference does it make to anybody?”

In any case, I decided all those years ago that I would do all I could someday to return Thomas’ star to him.

My father died in 1994. After the funeral was over and the guests were gone and before we all left town to return to our respective homes and as was the tradition in my mother’s family; my father’s belongings were placed on the dining room table. Each of us was invited to take what we wanted as a keepsake. I was the second oldest, so I got second pick. Thomas Moncrief’s star was the item I took from the table, put it into my pocket, and carried it back home.

Now, 23 years after my father’s death, it is time to fulfill this promise to myself and to redress this offense to our family. But how would I replace the severed stanchion? How would I re-attach the stolen star?

The Mechanics of Repair

In my mind, the star would have to be put under the torch or drilled in some torturous way to remove it from its stem and set it on a new one.

I thought of my friend, Stanley Crane. His background is in theater management – he was, many years ago, in charge of set construction for Hartnell College’s theater company – The Western Stage. As importantly, he was raised on his family’s farm in Yolo County, California. If Stanley doesn’t know how to make or repair something, you can be sure, he knows the right person to ask.

I showed Stanley the star. “Oh,” he said. “It’s screwed in.”

“What?” I asked.

“The stanchion. It’s screwed into the star.”

The star sat on my shelf for more than twenty years, and I had never noticed that the stanchion was screwed, not welded, to the grommets on its backside. This is why I needed Stanley.

“Let’s go see Albert,” Stanley said.

I had met Stanley’s nephew, Albert at parties. They are, so to speak, cut from the same cloth.

Albert teaches metal shop and farm-fabrication at Hartnell. We set an appointment and met with him the following day on campus.

Albert, tall and confident, strode along the corridor toward his office in jeans and a sports coat. We showed him the star and the stanchion.

“It’s screwed in,” he said immediately. Stan gave me a nod and wink. “No problem,” Albert continued. “Be at my shop tomorrow at noon.”

The following day, I arrived at Hartnell’s East Campus at 11:50 a.m. Albert had already freed the star from its broken mooring and was fashioning a new stanchion from a half-inch rod. He paused just long enough to greet me.

“The star is bronze,” he said, “but the stem is iron. We don’t have the exact size, but we can trim it on the wheel.” Albert smiled. ”I like what you’re doing,” he stated. “It’s a really cool thing.”

In no time, Albert had created a new stanchion and had the star attached. Now all I needed was a bucket of cement to set it in. With the help of my friend, Mike Scott, we had the iron bar lodged in cement before the evening was out. At last, I was ready for my journey to Emmetsburg, Iowa.

"There is rest in heaven"

My wife, Judi, and I started on our road trip in late July. We arrived in Emmetsburg on August 1. I had already contacted the local Catholic parish, whose staff managed St. John’s Cemetery. They offered support in re-interring the base of the star.

We met the grounds crew, Andy and Joe, in the late afternoon. A light breeze brought a bit of relief from the warm summer sun. Andy led us to the family tombstone with the names of Thomas and Lucy engraved on one side and the names of their son, John, and his wife, Mary, on the other. I asked Joe to dig the hole on the north side of the marker. We stood quietly and watched as Joe buried the bucket with its stanchion. I then stepped forward and, at last, fastened the star, returning it to its proper place beside Thomas William Moncrief’s grave.

Judi and I sang the poignant hymn, “Holy Ground,” as closure on this brief liturgy of restoration. The inscription on the tombstone reads, “There is rest in Heaven.” The sun fell closer to the earth, yet the breeze blew a bit stronger, leaving us refreshed and ready to begin our own journey back home.